A Swedish duo reimagine the appearance of time.

By Logan R. Baker

When the Swedish twosome known as Humans Since 1982 began working on what was to eventually become ClockClock 24, they didn’t set out to make a timepiece at all. It all started with a typography project in 2008 at HDK Göteborg, where Per Emanuelsson and Bastian Bischoff (the aforementioned pair) were still enrolled as postgraduate students.

“Playing with the idea of using clocks to create a moving typeface eventually led to the first sketches for ClockClock,” says Emanuelsson.

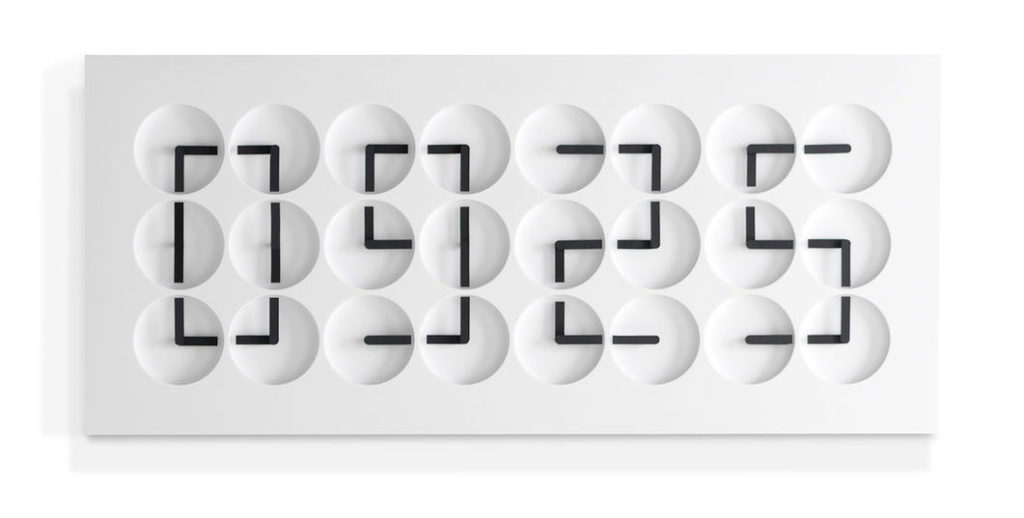

The original ClockClock and the ClockClock 24 make for an avant-garde approach to the traditional subject of timekeeping. The way it works in the ClockClock 24 is 24 analog wall clocks are coordinated to depict a digital read-out of the time. This ends up creating a dizzying display of motion that is quite captivating to watch. After developing the first prototype—with the assistance of an electrical engineer—in Emanuelsson’s dorm basement, the original ClockClock was soon picked up by Phillips auction house where it was purchased by a Russian tycoon. Soon thereafter, the pair decided to expand the operation and make their unique approach to telling time available to a global audience on the internet.

In addition to creating a innovative way of depicting the time, the two have advanced the way the age-old science of horology appears. By merging the two vastly different timekeeping displays, Humans Since 1982 ended up combining a methodology that has kept watch enthusiasts up at night ever since the quartz crisis and through today, where the digital era has left the time to be read in a series of numbers rather than as a physical representation of its constant passage. With all this change, it has left many wondering where to draw the line at what we can and cannot call a watch.

Of course, there can be no official answer to that question and it will be up for interpretation as long as we live, but the ClockClock does fulfill the kinetic desire we have when wearing a mechanical timepiece while executing its vision in a modern and approachable way.

“Our focus was always more on the ephemeral beauty of the passing of time than the reporting of time: in ClockClock the clock hands are liberated from their sole practical purpose of reporting the time—the clock hands also become dancers,” says Bischoff.

When they began working on what became the original ClockClock, Emanuelsson and Bischoff did begin to research horological history but they didn’t go digging through the notes of Abraham-Louis Breguet or John Arnold. Instead they sought their inspiration from an underappreciated source: the humble cuckoo clock.

ClockClock 24, $6,000-7,000; clockclock.com / moma.org